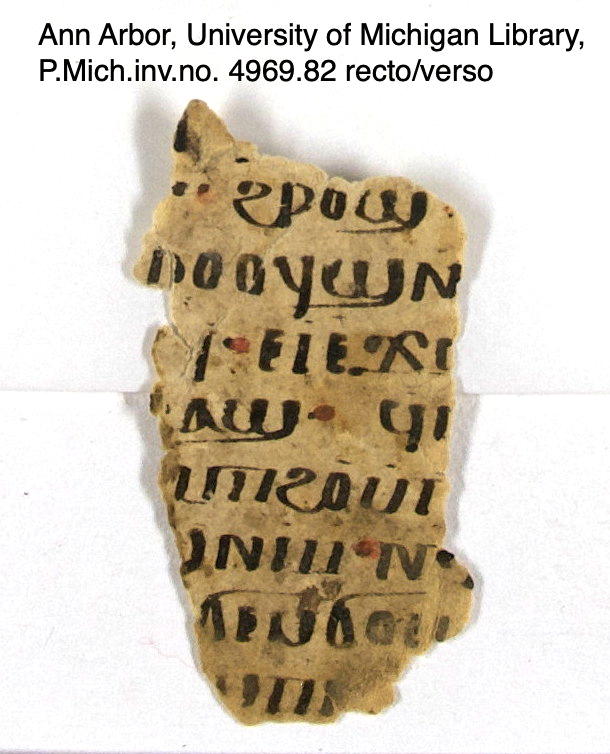

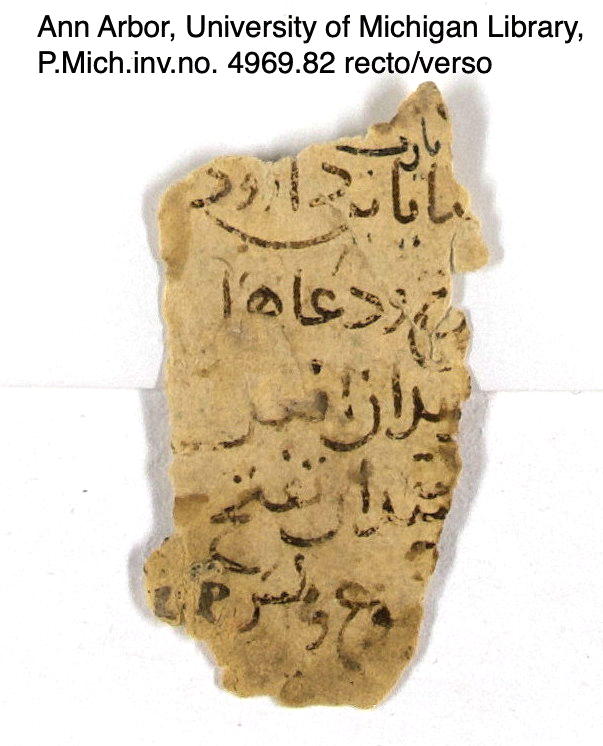

In November 2019, Diliana Atanassova and Alin Suciu visited Ann Arbor to sift through the several hundred non-inventoried fragments of White Monastery manuscripts in the University of Michigan Papyrological and Special Collections.[1] During their stay, they were able to sort out and identify some previously unknown Coptic fragments. Among those fragments containing biblical, hagiographical and patristic texts, one presented the particularity of bearing Sahidic text on one side and Arabic text on the other. The small paper fragment was assigned the Michigan inventory number P.Mich.Inv.no.4969.82. It is broken on all sides and contains eight partial lines of Coptic text on one side and five partial lines of Arabic text on the other (see the figures below). The Coptic text was easily identified as Luke 21,34–36 and the Arabic text as Matthew 20,31–34.

The presence of the two languages strongly suggests that the fragment belonged to a bilingual Sahidic-Arabic manuscript. To date, there are seven such extant Sahidic-Arabic manuscripts, three of which are Holy Week lectionaries[2] with readings from the Old and the New Testament. The fourth textual witness consists of six preserved folios bearing readings from the Old Testament only.[3] The fifth is a psalter,[4] and the sixth was identified by Alin Suciu as a fragment of 4 Ezra (= 2 Ezra 3–14).[5] The seventh is a liturgical codex in Sahidic with Arabic translations. Passages in Greek and Bohairic also appear in that manuscript.[6]

As Alin Suciu pointed out in relation to the Ezra fragment “such artifacts belong to very last stage of production of Sahidic manuscripts in Egypt.”[7] The similarity in script and decorative punctuation between the Ann Arbor fragment and the Holy Week lectionaries as well as the Ezra fragment is clearly visible. See as an example the online photographs in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana of the Holy Week Lectionary sa 16L. But while this likeness leads to the assumption that the Ann Arbor fragment stems from the same period – the end of the 14th or the beginning of the 15th century,[8] the slightly different Coptic hand is clear evidence that the new Ann Arbor fragment does not belong to any of the above Sahidic-Arabic manuscripts. This is also confirmed by the different Arabic hand.

The fact that the newly inventoried fragment bears texts from different Gospels points to a bilingual Sahidic-Arabic lectionary. Searching through the available lists and databases presenting Sahidic and Bohairic liturgical sources with biblical readings showed that both the Sahidic and the Arabic texts are acephalous and incomplete and most probably present the remains of the pericopae Luke 21,34–38 and Matthew 20,29–34, known in the Coptic liturgy.

The pericope Luke 21,34–38 appears in the Holy Week Lectionary among the readings of Tuesday at the 6th Hour of the Eve and can be found in 19 of the 20 witnesses considered by Oswald Burmester in his Lectionnaire de la Semaine Sainte.[9] It can also be read in the Bohairic rite during the Prayers of the Veil and the Night Prayers.[10]

The whole pericope Matthew 20,29–34 is attested in only one Bohairic manuscript (Paris, BnF, Copte 134, 1886 AD) and, what is more, among the readings of Palm Sunday. Rather interesting is the fact that the incipit of this pericope Mt 20,29 is preserved in the typika of the White Monastery MONB.WD, London, BL, Or. 3580 A.1r, l. 14 and MONB.AW, Wien, ÖNB, P.Vindob. K 9732r, l. 32.[11] It was recited on Saturday four weeks before Christmas.

All these clues and indications confirm the fact that we are dealing with a fragment from a Sahidic-Arabic lectionary which represents an eighth, previously unknown Sahidic-Arabic manuscript witness.

Although the identification of the texts can be considered certain, their liturgical Sitz im Leben remains to be investigated. The identification of the type of the new bilingual lectionary involves many difficulties that cannot be overcome for the time being, because the two Gospel pericopae do not appear together, not to mention follow each other in any of the extant types of lectionaries, be it Holy Week lectionaries, Lent lectionaries, Annual (Gospel) lectionaries or sabbato-kyriakai lectionaries. [12] Moreover, all the considerations mentioned above make it unfortunately impossible to conclude at present which text is recto and which is verso. Nevertheless, I am giving here the transcription of both texts to facilitate further investigation.

P.Mich.Inv.no. 4969.82 recto/verso

Luke 21,34–38

34[ ]

1 [ⲛⲧⲉⲡⲉⲧⲛϩⲏⲧ] ︥·· ϩⲣⲟϣ [ϩⲛ̄ⲟⲩⲥⲓ]

2 [ⲙⲛ̄ⲟⲩϯϩⲉ. ⲙⲛ̄ϩⲉⲛ]ⲣⲟⲟⲩϣ ⲛ̄[ⲧⲉⲡⲃⲓⲟⲥ]

3 [ⲛ̄ⲧⲉⲡⲉϩⲟⲟⲩ ⲉⲧⲙ̄ⲙⲁ]ⲩ̣· ⲉⲓ ⲉϫⲱ̣[ⲧⲛ̄ ϩⲛ̄ⲟⲩ]

4 [ϣⲥ̄ⲛⲉ 35ⲛ̄ⲑⲉ ⲛ̄ⲟⲩⲡ]ⲁϣ· ϥⲛ̣[ⲏⲩ ⲅⲁⲣ]

5 [ⲉϫⲛ̄ⲛⲉⲧϩⲙⲟⲟⲥ ϩⲓϫ]ⲙⲡϩⲟ ⲙ̄ⲡ̣[ⲕⲁϩ ⲧⲏⲣϥ̄·]

6 36[ⲣⲟⲉⲓⲥ ⲇⲉ ⲛ̄ⲟⲩⲟⲉⲓ]ϣ̣ ⲛⲓⲙ· ⲛ̄ⲧ̣[ⲉⲧⲛ̄ⲥⲟⲡⲥ̄]

7 [ϫⲉⲕⲁⲥ ⲉⲧⲉⲧⲛⲉϣ]ϭⲉⲙϭⲟⲙ [ⲉⲣ̄ⲃⲟⲗ ⲉⲛⲁⲓ̈]

8 [ⲧⲏⲣⲟⲩ ⲉⲧⲛⲁϣ]ⲱ̣ⲡⲉ̣ [ⲁⲩⲱ ⲉⲁϩⲉⲣⲁⲧ]

[ⲧⲏⲩⲧⲛ̄ ]

P.Mich.Inv.no. 4969.82 recto/verso

Matthew 20,29–34

31[ ]

ˊيا ربˋ

1 [قايلين ارﺣﻤ]نا يا بن داود

2 32[فوقف يســ]وع ودعاهما

3 [وقال لهما ماذا]تريدان ان افعل

4 [بكما 33 قالا له يا]سيد ان تفتح

5 [اعيننا 34 فتحنن ﯿ]سوع ولمس

[ ]

[1] For the history of the collection, see E.M. Husselman, “Manuscripts and Papyri”, in The Michigan Alumnus-Quarterly Review 35 (1928/1929), 622.

[2] sa 16L, Rome, BAV, Borg.copt.109, cass. XXIII, fasc. 99; sa 349L, Paris, BnF, Copte 102 and Borgia Copto 109, cass. 23, fasc. 98; sa 292L, Oxford, BL, Huntington 5.

[3] BC sa 145L, Oxford, BL, Copt. d. 2 (P) and London, BL, Or. 3579 A.5. Cf. K. Schüssler, Biblia Coptica 2.1, Wiesbaden (2012), 72–74.

[4] sa 2032 in the List of Coptic Biblical Manuscripts (LCBM, Münster and Göttingen), (BC sa 164), Napoli, BN, I.B.19.

[5] Paris, BnF, Copte 132(1), f. 32. Cf. A. Suciu, “On a Bilingual Copto-Arabic Manuscript of 4 Ezra and the Reception of this Pseudepigraphon in Coptic Literature”, in Journal for the study of the Pseudepigrapha 25.1 (2015), 3–22.

[6] LCBM sa 440L, Paris, BnF, Copte 68, f. 1–77 and Leiden, RMO, AES 40–60, one leaf (olim Ms. 89, Insinger 44).

[7] Suciu, “On a Bilingual Copto-Arabic Manuscript of 4 Ezra”, 9.

[8] Suciu, “On a Bilingual Copto-Arabic Manuscript of 4 Ezra”, 12.

[9] Cf. O.H.E. Burmester, Le Lectionnaire de la Semaine Sainte II, PO 25.2 (1943; Reprint Turnhout 1997), 475.

[10] Cf. A.A. Vaschalde, “Ce qui a été publié des versions coptes de la Bible. Deuxième groupe. Textes bohairiques. II. Nouveau Testament”, in Le Muséon XLV (1932), 117–156, 138.

[11] I received this information from Diliana Atanassova.

[12] Both pericopae are not found together in any of the manuscripts with Sahidic versions of the Gospels listed by various scholars, cf. Vaschalde, “Ce qui a été publié des versions coptes de la Bible. Premier groupe. Textes sahidiques. II. Nouveau Testament”, in Revue Biblique 29 (1920), 255–258; 30 (1921), 237–246.

Blogs

Blogs  Legutóbbi bloggerek

Legutóbbi bloggerek